Results from recent trials have changed surgical management of appendicitis and diverticulitis. The key recommendation now is for surgeons and patients to decide together whether surgery is the right choice, but this individualized approach poses challenges, said surgeons speaking at a panel at the 2023 annual meeting of the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons.

The panelists gave an overview of clinical trial results, along with their best practices for how to make shared decision making a reality in practice.

The Evidence: Acute Appendicitis

Since 1995, at least seven major trials compared surgery with antibiotics for adults with appendicitis. Recurrence rates were between 12% and 30% for patients treated with antibiotics, said Anne P. Ehlers, MD, MPH, an assistant professor of surgery at the University of Michigan, in Ann Arbor. As a result of these findings, surgical and emergency medicine organizations declared antibiotics a suitable alternative to surgery.

The reality is more nuanced, she said. In a randomized trial that followed patients for five years after their first episode of appendicitis, 39% of those who received antibiotics initially had an appendectomy (JAMA 2018;320[12]:1259-1265). The trial did not include patients with an appendicolith, in whom recurrence is even higher, she said. The presence of an appendicolith is associated with a nearly twofold increased risk for appendectomy within 30 days of initiating antibiotics (JAMA Surg 2022;157[3]:e216900).

Patients often chose to get an appendectomy after antibiotics because of worsening symptoms, according to a follow-up analysis of data from the CODA trial, a large, randomized study (JAMA Surg 2022;157[3]:e216900). Three-fourths of patients said they wanted surgery because their condition worsened, and about one-fifth chose surgery for nonclinical reasons, including concern for recurrence and cancer.

“Definitely not everyone needs surgery right away,” Dr. Ehlers said. But the decision depends on patient factors: “Are they trying to get back to work? Are they nervous about surgery? Those are the types of things to pay attention to when you’re talking to your patients.”

Pregnant patients were not included in these trials, so there is little information about individual risk in pregnancy, she said.

Shared Decision Making: Appendicitis

Caroline Reinke, MD, an associate professor of surgery at Carolinas Medical Center, in Charlotte, N.C., said there are three necessary steps for shared decision making to take place: The care team must understand the recommendations; the care team must share this information, overcoming their own beliefs, inexperience with nonoperative management or competing priorities; and patients must be able to understand the information, despite fear of recurrence and misinformation.

But the reality of hospital care makes this information exchange difficult, she added. Patients who arrive in the emergency department (ED) with appendicitis meet the emergency medicine team and other healthcare providers before they see a surgeon. These care team members help prepare patients for what’s ahead. “Not everyone in the team has to know all the data, but they have to be able to say that we are having conversations and the surgeon will come talk to you about the options,” she said.

For patients who initially present to a freestanding ED where treatment decisions are made via phone communication, the surgery team sometimes meets a patient with appendicitis for the first time in pre-op holding. “That’s a very different place to have this conversation.”

Dr. Reinke said surgeons can improve these discussions by directing patients to www.appyornot.org. The decision tool can help patients identify their priorities as they select a treatment plan. It is being studied by investigators for the TRIAD (Treatment Individualized Appendicitis Decision Making) program, for which Dr. Reinke is the primary investigator.

Patients who share in decisions regarding their treatment are likely to be more satisfied with their care, and experience less anxiety and decision regret. They also have better adherence to medical recommendations and better outcomes, she said.

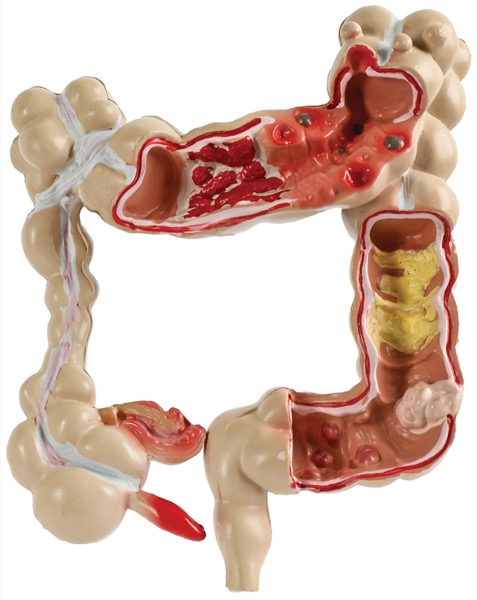

The Evidence: Complicated Diverticulitis

Guidelines from SAGES and the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons no longer recommend that patients undergo surgery after a specific number of episodes of diverticulitis (Surg Endosc 2019;33[9]:2726-2741; Dis Colon Rectum 2020;63[6]:728-747).

Instead, both guidelines state that the risk for recurrence increases with each episode, and patient options should be considered every time diverticulitis occurs.

The risk for recurrence is higher with complicated diverticulitis than uncomplicated diverticulitis. About 25% to 33% of patients are expected to have a second episode within five years, said Virginia O. Shaffer, MD, a professor of surgery at Emory University, in Atlanta.

But recent evidence shows that nonoperative management can be safe in the long term for many patients with complicated diverticulitis, she said. It “can be an acceptable risk profile with acceptable long-term outcomes in the appropriate patients, but it’s very nuanced.”

One of the largest studies to date of conservative management in complicated diverticulitis found no difference in adverse outcomes between patients who underwent an interval elective resection and those who were conservatively managed (JAMA Surg 2020;155[7]:600-606). Investigators looked at the long-term outcomes for 18,900 patients in Switzerland and Scotland who had complicated diverticulitis managed nonoperatively between 2005 and 2015. Patients in Switzerland were five times more likely to undergo an interval elective resection: 23.7% versus 4.5%. But the outcomes of patients in the two countries were remarkably similar. Deaths after urgent readmission for recurrent diverticulitis occurred in 104 patients (0.8%) in Switzerland and 65 (1.3%) in Scotland.

Dr. Shaffer cautioned that many studies of complicated diverticulitis do not evaluate patient-reported outcomes.

Shared Decision Making: Diverticulitis in the Elective Setting

Healthcare teams have not done a good job historically at shared decision making with patients with diverticulitis, said Andrea Petrucci, MD, MEd, an assistant professor of surgery at Cleveland Clinic Florida, in Weston. In one study, 27.1% of patients with diverticulitis said physicians led the decision making over their illness, but this was only desired by 8.7% of patients (J Surg Res 2021;261:159-166). Patients also said they experienced high rates of decision regret at 32%. For other conditions, decision regret is experienced between 9% and 14% of patients, Dr. Petrucci said.

Deciding between surgery and conservative treatment can be a difficult decision for patients, she added. Elective colectomy for diverticulitis has greater morbidity and mortality than colectomy for cancer, and 27% of patients with diverticulitis still have persistent symptoms after surgery (JAMA Surg 2013;148[4]:316-321). Moreover, most patients have an excellent response to conservative treatment, with only 3% to 5% of patients requiring an emergency colectomy or colostomy (Arch Surg 2005;140[7]:681-685; Dis Colon Rectum 2020;63[6]:728-747).

The decision about management is further complicated by studies that show an improved quality of life with elective resection over conservative management (Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;2[1]:13-22).

“My take-home message for uncomplicated disease is that you need to assess the operative risks and the coexisting conditions,” Dr. Petrucci said. “How bad are their attacks? Are they at the hospital every month being admitted? Are they missing work? Are they missing school? Are they traveling a lot for work? These are all things to take into consideration.”

For diverticulitis with an abscess, surgeons should also consider the size of the abscess in discussions with patients, she said.

She encouraged surgeons to plan to spend extra time speaking with patients with diverticulitis and follow up frequently by phone. “Because it’s not a straightforward decision,” she said.

Address Language Barriers

Healthcare teams need to do more to address language barriers when speaking to patients with limited English proficiency, said Elina Serrano, MD, a PGY-4 general surgery resident at the University of Washington, in Seattle.

Twenty-five million people in the United States have limited English proficiency, but studies show that one-third of hospitals do not offer language services (Health Aff [Millwood] 2016;35[8]:1399-1403). Physicians use interpreters with less than one-fifth of patients with limited English proficiency (J Gen Intern Med 2011;26[7]:712-717). This is true even in discussions over high-risk care like surgery; in Ottawa and Toronto, surgeons said they often used their own limited non-English language skills or relied on bilingual staff or family members to obtain informed consent before surgery (J Am Geriatr Soc 2021;69[8]:2358-2361).

But there are “very concrete actionable steps” that healthcare teams can make that improve care for patients with limited English proficiency, Dr. Serrano said. At her hospital and clinic, bilingual staff must undergo a proficiency assessment; all patients who prefer to communicate in a language other than English can access an interpreter; 10 to 20 minutes are added to appointment times with an interpreter; the interpreter must be present before the physician enters the room and, at the end of the visit, is asked whether the medical team has missed anything; and clinicians are taught how to work with medical interpreters.

Limited English proficiency has been linked to longer hospital stays; a greater risk for surgical infections, falls and pressure ulcers; more surgical delays and readmissions; and decreased satisfaction with care, Dr. Serrano said.

“Provision of language services and culturally sensitive care in a timely manner can not only alleviate patient distress but can also enable our patients with limited English proficiency to make decisions that really align with their goals of care,” she said.